Note: I have made references throughout this blog to timings for certain highlighted moments (e.g 0:03 of track 1) – this is in relation to a recording of the work I will provide a link to below (follow along should you so desire).

Music has a long-running debate which has seemingly for time immemorial caused division amongst its adherents. Should it be viewed purely and absolutely through the lens of its own intrinsic elements (harmony, counterpoint, rhythm, thematic and motivic development etc.) or is it capable of conveying ideas and narratives outside of itself or in other words to paint pictures in sound? In the 19th century this debate raged on, at times ferociously, as the music of central Europe was divided into two rival camps, one comprising the so-called ‘conservatives’ Johannes Brahms, the critic Eduard Hanslick and their circle who preached the gospel of absolute music; the other being composed of the ‘progressives’ Richard Wagner and Franz Liszt (with his tone poems) who believed music should now be entwined with narrative and influences from other art forms. But what of the much younger Gustav Mahler, who came of age during this era of rival visions?

“A Symphony must be like the world – it must encompass everything”

Or so Mahler is famously reported to have said to the Finnish composer, Jean Sibelius, during their meeting. This seems like quite a bold claim to say the least, but in essence what Mahler meant by this was he wanted his symphonies to be more than just musical forms with their own internal logic but rather works capable of reflecting ideas, feelings, and even places to such an extent that they could encompass the whole world. So, it would appear at least from this quote that Mahler was not strictly speaking in the absolutist camp. He did of course continue to utilise traditional musical forms (while stretching them to their limit), after all, the piece I will discuss today is a symphony not a tone poem. One thing, though, is undeniable, Mahler appeared to make a conscious effort in all his symphonies to bring in sounds and references that drew listeners outside the realm of the concert hall and into the world at large. As such I will attempt to incorporate these references in my discussion of his 3rd Symphony in D minor. Ultimately, many will dislike such an analysis that draws from extra-musical themes, but I feel with Mahler it is absolutely necessary to do so.

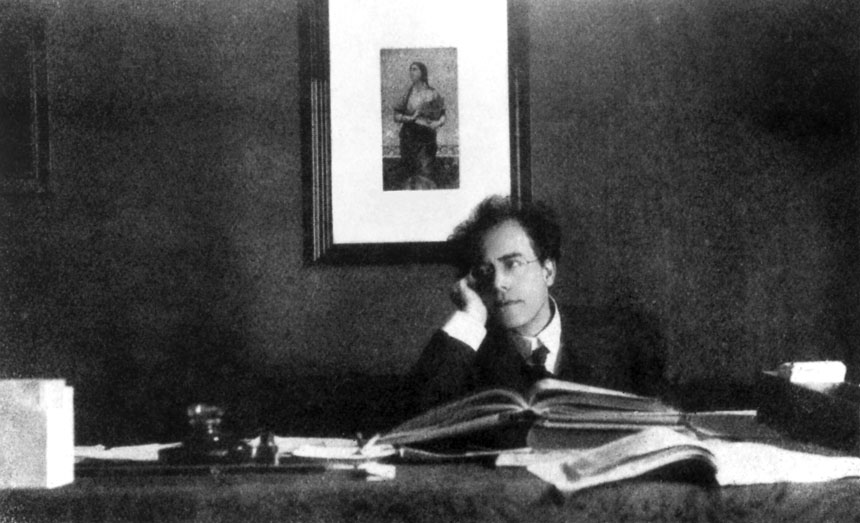

Wagner and his father-in-law Liszt Brahms pictured bottom right sat next to Hanslick Mahler pictured in 1881

But first another enlightening anecdote, this time from the memoir of Mahler’s protegee Bruno Walter, describing an incident on the latter’s visit to Steinbach am Attersee where the composer had a villa and composing hut:

“I arrived by steamer on a glorious July day; Mahler was there on the jetty to meet me, and despite my protests, insisted on carrying my bag until he was relieved by a porter. As on our way to his house I looked up to the Höllengebirge, whose sheer cliffs made a grim background to the charming landscape, he said: ‘You don’t need to look — I have composed all this already!”

More on the Höllengebirge later, for now it suffices to say that Mahler clearly acknowledged a close connection between the work he was composing at the time of this anecdote (in fact his 3rd symphony) and the landscape around Steinbach am Attersee. To truly grasp this one must really visit the Salzkammergut region and the lake and town in question, but pictures provide a good impression of what might have inspired the music, if still a tame one in comparison to the real thing.

In our interpretation of this work, we are aided by the fact that Mahler originally constructed a programme for the symphony. It seems to illustrate a story arc from an initial awakening of nature, through a description of the many aspects of creation, before concluding with a vision of divine love:

1. Pan Awakens – Summer Marches In

2. What the Flowers and Meadows Tell Me

3. What the Beasts of the Forest Tell Me

4. What the Night Tells Me

5. What the Morning Bells Tell Me

6. What Love Tells Me

Movement 1. – Pan Awakens – Summer Marches In

The symphony begins with a statement by 8 horns in unison, a kind of incantation to bring the symphony to life (0:03 – 0:28 of track 1). Then, begins a descent into a slow introduction, which sounds like the first elements of matter groping towards a more substantial existence (1:20 to 5:10 of track 1). Indeed, Mahler described to his confidante Nathalie Bauer-Lechner the ‘eerie’ way in which the music illustrated ‘life gradually’ breaking ‘through, out of soul-less, rigid matter’. The score indicates this passage should be ‘Schwer und Dumpf’ (heavy and stifling), and throughout motivic fragments played by different instrument groupings struggle to break out into full melodies. In a letter to the soprano Anna Bahr-von-Mildenburg, Mahler entitled the first part of the movement ‘what the stony mountains tell me’. Perhaps, he was inspired by the stony cliff face of the Höllengebirge that could be viewed from his composing hut when he wrote this turgid, primordial music.

Two of the themes of this movement seem oddly out of place in a formal 19th century symphony. The first is a jaunty melody, which would have perhaps been more at home in the popular music of Mahler’s time (first heard at 5:28 of track 1). Indeed, it has a surprising but probably coincidental affinity to the ‘Be our Guest’ melody from Walt Disney’s ‘Beauty and the Beast’ (1946). The other is like a march for a military band, no doubt similar to marches that were performed in the town square of Mahler’s hometown of Iglau, Bohemia (first heard at 10:02 of track 1). Both illustrate Mahler’s tendency to absorb music from other areas of life and utilise them in his symphonies. The effect of this is a music which at times is unusually raucous for a symphony, for example in the passage (from 20:04 – 23.24 of track 1) immediately preceding the recapitulation! Overall the movement appears to chart the struggle for life to break free from inanimate matter or to use another metaphor: for the chaotic, Bacchic forces of Summer to overcome those of stupefying winter.

Movement 2. What the Flowers and Meadows Tell Me

What do the flowers tell us? They tell us that the world is born again each spring anew in purest simplicity. Flowers represent beauty and life at its most transient and frail, but also its most irresistibly lovable. They are a source of gentle consolation in our lives made tired by work and worry. So, after the gigantic first movement, Mahler now offers us a respite both musically and pictorially. Broadly speaking there are two alternating and contrasting subjects, the first a relatively static and graceful minuet (first heard at 0.02 – 2:16 of track 2), the other comprising a series of frenzied kaleidoscopic episodes which seem to run wild like blossoms blown in the wind (first heard at 2:16 – 3:09 of track 2). This movement reflects Mahler’s superb orchestration and his command of the vast forces at his disposal which he is able to use at times as if they were a chamber ensemble. It is Mahler’s tribute in music to one of the simplest but most precious forms of life. The composer who spent much of the year hard at work as a conductor coping with the great demands of the concert season must have had a special place in his heart for the alpine blooms that greeted him on his summer composing retreats.

Movement 3. What the Beasts of the Forest Tell Me

Mahler composed almost exclusively in two forms: the symphony and song. Song is one clear way in which music can take on meanings outside of itself as it is fitted to texts which express concrete ideas and narratives. But one further way is to reference these songs in purely instrumental music. Mahler frequently made use of themes from his songs in his symphonies, as a way to subtlety aid interpretation. In this scherzo movement, simply brimming with playful energy, Mahler makes use of the melody from one of his earlier songs ‘Ablösung im Sommer‘ (see below video). The song is a classic example of Mahlerian irony, the words tell with nursery rhyme innocence of how the cuckoo has died and been replaced by the Nightingale. The theme of death then is introduced to this symphony almost mockingly. In this way Mahler adds an extra level of grotesqueness to this scherzo which rampages on much like ‘the Beasts of the Forest’ might, without a care in the world for the cuckoo who has died.

The composer’s masterstroke in this movement is to include as a contrasting section the famous ‘Posthorn solo’ (first heard at 6:18 of track 3). The Posthorn was an instrument carried by mail carriers in the Austro-Hungarian Empire, and its sound would have been well known to the symphony’s original audience. Mahler specifically calls for use of the Posthorn, an instrument foreign to the concert hall (most modern performances will utilise either a muted trumpet or a flugelhorn). The composer calls for the Posthorn to be played off stage and to be heard as if from a distance. The effect is a contemplative passage which emanates wistful nostalgia, and provides a tremendous contrast with the rest of the movement’s hurly-burly. It is possible that the inspiration for this section was Nikolaus Lenau’s poem ‘der Postilion’, which tells of a carriage guide who continually sounds his Posthorn at the gravesite of a departed friend. This, then, is perhaps humanity’s perspective shown for the first time, a species with a unique comprehension of its own mortality. The Posthorn solo twice interrupts the main scherzo material, but the latter section returns each time, before the movement concludes with a startling orchestral eruption (from 16:53 of Track 3 onward). The tension remains unresolved.

Thomas Hampson performing ‘Ablösung im Sommer’

Movement 4. What the Night Tells Me

We have seen so far how this symphony has charted a path in music from inanimate and turgid matter, through to the world of plants and flowers and finally to the beasts of the forests. We had seen the first signs of conscious life with the Posthorn solo in the third movement, which illustrated an awareness of suffering and mortality. It is at this stage that Mahler introduces the human voice for the first time in this symphony. The movement begins with utmost mystery, before the alto soloist delivers a text from Friedrich Nietzsche’s ‘Also Sprach Zarathustra’:

|

|

Mahler had mixed views about Nietzsche to say the least, he later told his wife, Alma, to burn her copies of the philosopher’s books, but at the time of composing this work he appears to have been highly influenced by his writings. In fact he considered giving the symphony a title of the ‘Joyful Science’ (after Nietzsche’s work of the same name). The text used in this movement describes how sorrow is deep, but joy deeper because sorrow seeks only annihilation while joy seeks a deep eternity. Throughout the movement Mahler has the oboes mimic bird calls which he has marked in one sketch as ‘Der Vogel der Nacht’ (a bird closely associated with the theme of death).

Movement 5. What the Morning Bells Tell Me

From this warning addressed to man at midnight, we now enter the joyful world of angels at the dawning of a new day. The composer sets a song (‘Es Sungen drei Engel’) from ‘Des Knaben Wunderhorn’ (or the ‘Youth’s Magic Horn’, a collection of folk songs assembled at the beginning of the 19th century which were close to Mahler’s heart) for a children’s and women’s chorus and the alto soloist. The children’s chorus imitate the sounds of bells by singing ‘Bimm Bamm’, while the song’s text is divided between the women’s chorus and alto soloist. The text describes the importance of faith in gaining forgiveness. It is not clear whether or not this setting of the song is meant to be entirely sincere, but considering Mahler indicates in the score that it should be ‘keck im Ausdruck’ (‘cheeky in expression’) it appears probably not. The composer was, after all, not to convert to Catholicism until a year after he completed this work in 1897 and then only to gain the directorship of the Hofoper in the notoriously anti-Semitic Vienna. This movement, then, forms the perfect light prelude for Mahler’s true spiritual thoughts which are to be expressed not in words at all but rather in music alone.

Movement 6. What Love Tells Me

It is pointless to attempt much of a description of this majestic movement which unfolds over a series of variations in which conflict must play its part, but which nevertheless must end in the most triumphant D Major. Mahler expressed the meaning of this movement in one simple phrase:

“Father, look upon my wounds! / Let no creature be lost!”

Postscript

Mahler decided to not publish the programme in the end. He concluded that although it had served as a useful scaffolding device for himself, ultimately it should not constrain listener’s interpretation. Bearing that in mind, how should we approach all the detail I have discussed in this blog. I would suggest read it, absorb it, allow it perhaps to form as a useful outline in your mind, but do not let it constrain your interpretation of this music.

Mahler would increasingly move away from programmatic music, he did not design programmes for his later symphonies. That is not to say he ceased to bring musical elements traditionally deemed unsuitable for the concert hall into his music. He always was and would remain a radical. But, unlike, his friend Richard Strauss, he had never completely turned his back on abstract music and the symphony. In fact it was through his redesign of the symphony that the form was brought into a new century. For this reason, along with many others, Mahler must be considered amongst the very greatest composers.

Written by Nick Jenkins

Here is the recording upon which the timings are based, you are more than welcome to choose your own performance but please note the timings could be very different if you do: