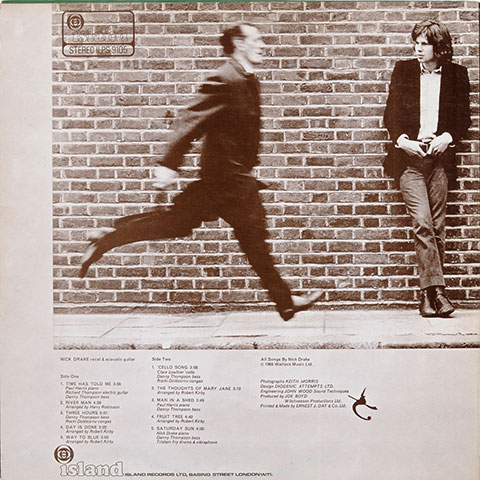

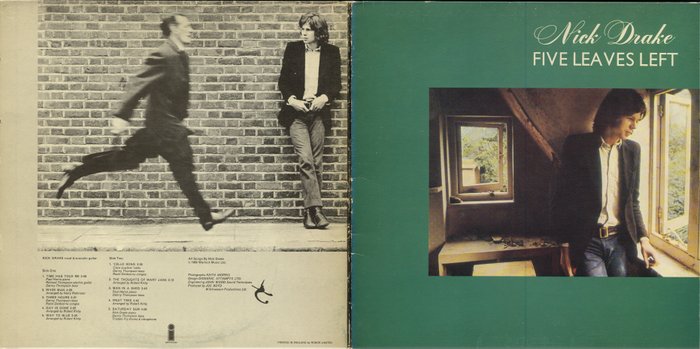

On 3rd July 1969, Nick Drake’s debut album, ‘Five Leaves Left’, was released . It sold poorly for the times, sales totalling about 6,000 records. A combination of Drake’s reluctance to tour, bad luck, and perhaps the complexity of the music meant that he was far from an instant hit. It was only after his death, at the age of 26 from suicide, that a substantial following began to grow. As the lines of the penultimate song on the album had so eerily predicted:

‘Fame is but a fruit tree

So very unsound.

It can never flourish

‘Til its stalk is in the ground.’

Fast forward almost half a century to December 2016, a date of considerable less importance to the world (but of tremendous personal significance for myself), and to an Oxfam charity shop in Balham, south west London, when I was first shown a recording of Drake’s music. It was for me an instant hit. A number of things were immediately recognisable in the music, first of all the sensitivity of the Drake’s voice. I had never heard someone sing so softly and yet with such clarity. Secondly the skill and complexity of the guitar playing. Finally there was the poetry of the lyrics. A number of the lines already stood out to me like this one from ‘Time has told me’:

‘Time has told me

You came with the dawn

A soul with no footprint

A rose with no thorn’

Nick Drake (1948-1974)

That day I rushed back home to buy Five Leaves Left on Itunes (remember this was B.C. – Before Cedric, and consequently no Deezer). The album still stands out to me as an all time favourite, which is why I am so grateful for the honour of paying to tribute to it. A number of aspects are worth mentioning besides the enormous talent of Drake himself. The string arrangements are stunning, all completed by Robert Kirby (a friend of Drake’s from Cambridge), aside from the one on ‘River Man’. The supporting musicians, assembled by legendary record producer Joe Boyd, are incredible and the recording itself is superb, thanks in large part to sound engineer John Wood.

Years later, John Wood (left) and Robert Kirby (right) on a documentary discussing their friend Nick Drake’s music and life

I think to give you a glimpse as to why this album is so dear to me, I should discuss some of the songs in greater detail. The opening track ‘Time has Told Me’ is a particular favourite of mine, I have always loved the twangling electric-guitar of Richard Thompson (from band Fairport Convention) on this track, and Drake’s lyrical delivery. The words themselves appear to sum up a love that could not be, and there are some tremendous insights like this one:

‘Your tears they tell me

There’s really no way

Of ending your troubles

With things you can say’

Then there is ‘River man’. Perhaps, the very greatest on this album, and possibly the best Nick ever wrote. It’s in 5/4 time, established throughout by Drake’s faultless guitar line, giving the song its asymmetrical but constant rhythm, like the flow of a river. Composer Harry Robertson provided the string arrangement this time (the young Kirby felt uneasy arranging in 5/4 time). Drake mentioned composers like Ravel and Debussey as a template for the arrangement, and no doubt this influence can be detected by the cognoscenti, but it is also worth mentioning that Robertson was credited as composer on a number of horror films at the time. Perhaps this is in part what gives the arrangement such a haunting feel. The lyrics expand on this atmosphere, with lines like:

‘Betty said she prayed today

For the sky to blow away’

There clearly is a macabre feel to the song, and it’s not surprising that people have interpreted the ‘River Man’ of the title as Charon, the boatman of the Stygian flood that divides our world from that of Hades.

Another favourite of mine is ‘Fruit Tree’. This time the arrangement is by Kirby, who said in an interview that this was just about his favourite he did for friend Nick. I would generally agree (which is a tough call given the high quality of his other arrangements). His use of the oboe and cor anglais in this song is particularly impressive and adds to the wistful melancholy.

Fruit tree has some of the best poetry of the album. Its tempting to read into the words a kind of premonition of the Nick Drake story. A tale of fame that was unsound because it could only truly flourish after his death. Yet when Drake recorded this album we know he was still fairly confident of success. It’s better to see in it a young man, wise beyond his years, steeped in the poetry of the English Romantics and French symbolists, making a universal statement, with language such as this:

‘Safe in the womb

Of an everlasting night

You find the darkness can

Give the brightest light.

Safe in your place deep in the earth

That’s when they’ll know what you were really worth’

The Drake family gravestone in Tanworth-in-Arden, Warwickshire, both parents outlived their child

Great art has the power to change us, or so they say. But sometimes with our favourite artists we find they have not changed us, but rather that they have acted as a mirror, reflecting back to us an undistorted image of ourselves. I have found this to be the case with Nick Drake. I do not believe I have changed after listening to his music, rather I believe it has always had such a strong effect on me precisely because it has spoken to me as I am, not as I might be. All art is a game at communication, and its aim is the same no matter the medium: to let us know we are not alone. For myself and many others since his tragic early death, Drake’s music has helped us feel that we are not alone. I hope that this article will encourage someone new to discover Nick. Perhaps, they will find as I have found, that he is:

‘a rare, rare find

A troubled cure

For a troubled mind’.