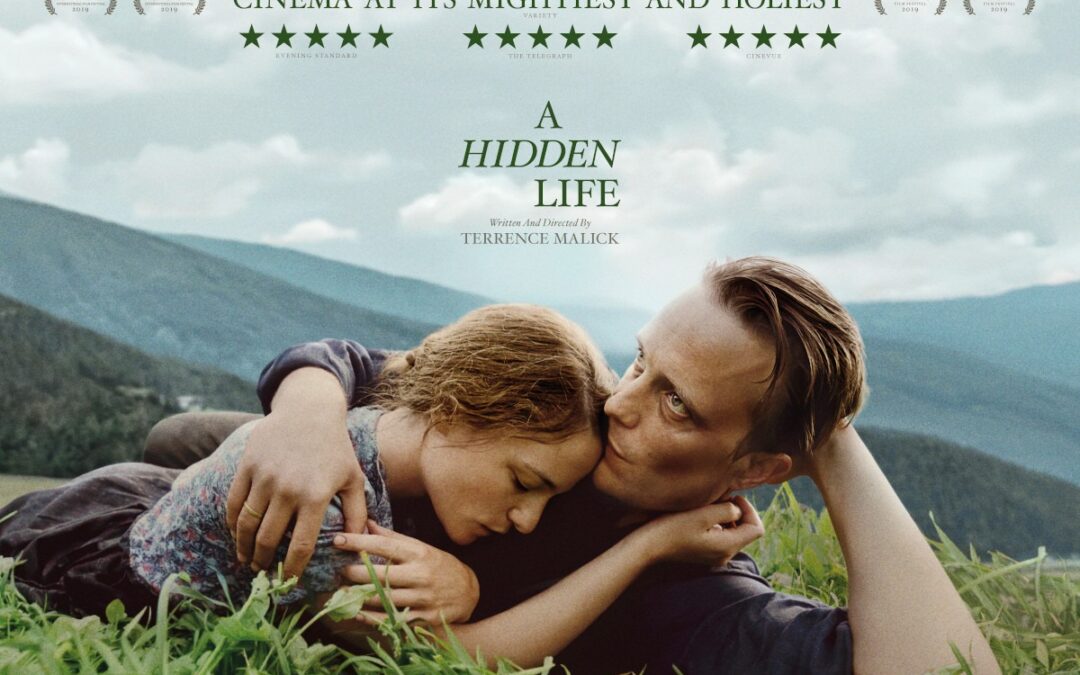

During the July heatwave, I yielded to the badgering recommendation of a good friend and invited Cedric and Nick to join me in watching A Hidden Life. Sitting in the stifling heat in stunned silence after the film, we all agreed that it was a devastatingly beautiful work of art that would stay with us for the rest of our lives.

A Hidden Life takes its title from George Eliot’s Middlemarch: …for the growing good of the world is partly dependent on unhistoric acts; and that things are not so ill with you and me as they might have been, is half owing to the number who lived faithfully a hidden life, and rest in unvisited tombs. Eliot in turn derived the phrase from St Paul’s Letter to the Colossians: Set your minds on the things that are above, not on the things that are on earth, for you have died, and your life is hidden with Christ in God (Colossians 3:2). Both Eliot and St Paul are saying that being a disciple of Christ is not merely about “being nice”; it ushers in a new life and transforms us, calling us to live not for fame or recognition, but for God. Encountering Christ and living in his light means that while we have a duty to share that light with others, we also live a ‘hidden life’ with him that is often contrary to the life that the world tells us we ought to live.

Without resorting to dialogue, Diehl conveys untapped reservoirs of doubt and torment over what his principles mean for his family. When, in the second half, Malick leans into the Christ parallels in the story, Diehl always keeps Franz human and grounded. Empire

The film follows the extraordinary choice made by Blessed Franz Jägerstätter as a result of this ‘hidden life’ with Christ. Franz was an Austrian farmer who worked the land in the small village of St Radegund to support his wife Franziska (or Fani) and their three daughters. When war broke out, Franz refused to swear allegiance to Hitler or fight for him, and as a result was arrested, imprisoned, and eventually executed. His family faced hardship without him, both because they had lost a husband and a father and because the villagers saw Franz as a traitor and refused to help his family. Scenes are cut between Franz’ imprisonment and Fani’s constant struggle on the farm, narrated by their letters to each other. Their love for God and each other is the burning link between Franz’ bleak, solitary cell and the sublimity of the mountainside farm in St Radegund. A question asked repeatedly throughout the film is, ‘what is the point of Franz’ refusal to fight?’ Brought up before various officials, Franz is repeatedly asked what he thinks he will achieve by objecting to the Nazi regime.

Fani’s sister, who lives with them, asks how he can desert his duty to his family, who are left helpless without him, for the sake of his principles. One memorable exchange occurs near the end of the film, when Franz is talking to a judge who, like Pontius Pilate, seems to have the inkling that the man in his charge is in fact just and should be set free. The judge asks, ‘do you judge me?’, a question Christians are often asked. Franz replies that he does not, and explains humbly, ‘I don’t know everything. A man may do wrong, and he can’t get out of it to make his life clear. Maybe he’d like to go back, but he can’t. But I have this feeling inside me, that I can’t do what I believe is wrong. The judge asks, ‘Do you have a right to do this?’, to which Franz replies, ‘Do I have a right not to?’ The “results” in an earthly sense of Franz’ refusal to co-operate with evil are beside the point.

The right thing is the right thing; it is not necessarily helpful to think of what we will “achieve” by following our consciences, but simply to follow them. This radical choice is presented to us not always on the scale of the decision that Franz faces, but in the everyday fight within ourselves. As Eliot writes, faithfulness in things that seem, and often are, insignificant in a worldly sense, really does count for the flourishing of goodness in the world. Naturally, we were all in awe of this film, which was beautiful in every way possible. Every scene merited a closer look and immersed us in the Jägerstätter’s inner scenery.

But this is the filmmaker on sublime form, putting his artistry and obsessions at the service of something frighteningly relevant. Empire

The questions posed by this story are not comfortable ones, but they are necessary. Cedric and I were particularly moved by the love of husband and wife for each other, and their knowledge that their love for each other is a reflection of and a means to love God. Real love often looks more like crucifixion than a walk in a meadow, and A Hidden Life offers a stark reminder of the call to love, even unto death.